I took a break from writing fictional prehistory so my husband and I could tour a real, live archaeological site this weekend. And, of course, I came away awash in facts and guesses about what made these ancient people tick.

The site in question is Hopeton Earthworks, located just across the river from the contemporaneous Mound City Earthworks in Chillicothe. In fact, our guide — Dr. Bret Ruby — suggested that we should really think of these two areas as facets of the same site. Mound City was used for burials while Hopeton appears to have been used a “World Center shrine.”

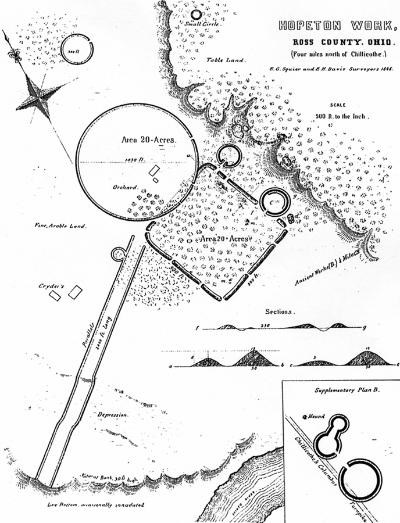

That analysis is based on the work of modern Native Americans, who speak of sites like this as being models of the universe. Specifically, the long double line at the bottom of the picture above represents two quarter-mile earthen walls that point to sunset on the winter solstice. This seasonal focus is common at similar sites, like the Calendar Mounds at Fort Ancient. Dr. Ruby suggested that Hopeton Earthworks may have been built as an “earth naval” meant to capture or channel the power of the solstice sun.

That part is guesswork, but there was plenty of rock-hard data present…quite literally. This summer, the archaeologists are excavating the remains of earthen ovens, which are currently found via machinery that senses magnetic anomalies in soil. In the past, these same ovens were often discovered by walking across tilled farmland and looking for fire-cracked stones like the one shown above.

What’s a fire-cracked stone? Let me back up and explain about earthen ovens. Hopewell people dug pits in the soil, filled them with wood, lit fires, then piled stones on top. The stones sucked up the fire’s heat then released it more slowly, often cracking along weak points in the rock in the process. The result is stones with multiple flat faces like the one pictured above. You don’t usually find this shape in non-human-impacted areas.

At the Hopeton Earthworks, fire-cracked rocks are very common, but they aren’t found everywhere. Instead, people appeared to keep their cookfires at the edge of the raised terrace that encircles the site, out of the floodplain but far enough away from the earthworks so they weren’t muddying the sacred with the profane. In other words — no trash in church!

There was, however, trash in the ovens…and archaeologists were excited to find it! The flint bladelet above was found the same day of our tour, the prismatic cross-section proving that the knife was knocked off a core using a very specialized Hopewell technique. This particular blade never got utilized, but our leader said that similar blades were used to shave hair into elaborate hairstyles. Fashion was a thing in Ohio in 0 BC.

So was art. The reflective shard on the other side of the deer bone in the image above is a chip of mica that might have been discarded while making ceremonial objects like images of birds and hands. Mica isn’t commonly found in Ohio, however, so this shiny rock would have been carried in from the mountains of North and South Carolina.

How did mica — and other distantly sourced materials like shells and obsidian — make its way to Chillicothe? I’d always understood that the Hopewell people had a farflung trade network. But Dr. Ruby made the excellent point that materials clearly moved to Ohio, but none seemed to make their way back out. Wouldn’t trade result in Ohio flint and other materials being discovered in North and South Carolina (among other places)?

Instead, our guide suggested two hypotheses for how this mica arrived in the Hopewell epicenter. Possibly Hopewell people went on long journeys, bringing home materials like mica to be incorporated into their ceremonial sites. Or perhaps Native Americans from other parts of the continent traveled to Chillicothe just like my husband and I did, bringing gifts of their local mica in exchange for viewing the sun through Hopeton’s quarter-mile earthen tunnel.

There’s so much more to share (like wood-henges purposefully dismantled and mounded over to hold power in the earth). But I’ll end with one last factoid:

- The clear quartz crystals sometimes found at Hopewell sites were tied as the hardest materials in the Hopewell world. What was the other material in first place? Beaver teeth!

Okay, now back to work on my novel. Olivia was in quite a bind when last I visited her. I guess I’d better help her out.