A few weeks ago, I was thrilled to notice a talk on shifters being planned at my library. It turns out that local author John B. Kachuba had researched the topic extensively while planning out his new release — Shapeshifters: A History. I took copious notes so I could share his lecture with you!

Kachuba takes a very inclusive view of shifters, starting with cave paintings from thousands of years ago that seem to represent animal-human hybrids. While we can’t know what prehistoric people were thinking, modern studies of the Yukaghir people in Siberia suggest that these cave paintings might represent ceremonies in which shamans mentally transformed into animals to assist in planning hunts.

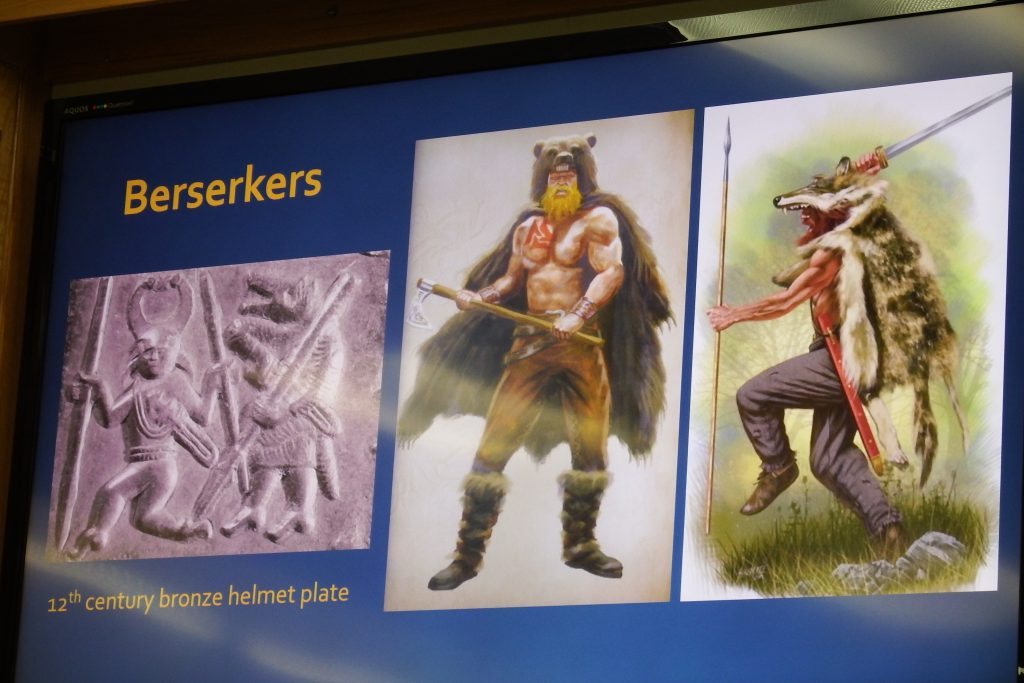

The natural successor of this belief is the Scandinavian berserkers from the eleventh and twelve centuries AD. Fighters donned hides of bears or wolves and, like the shamans of old, believed that they became as invincible as that animal in battle.

(To me, this has clear fictional potential. Berserker werewolves, anyone?)

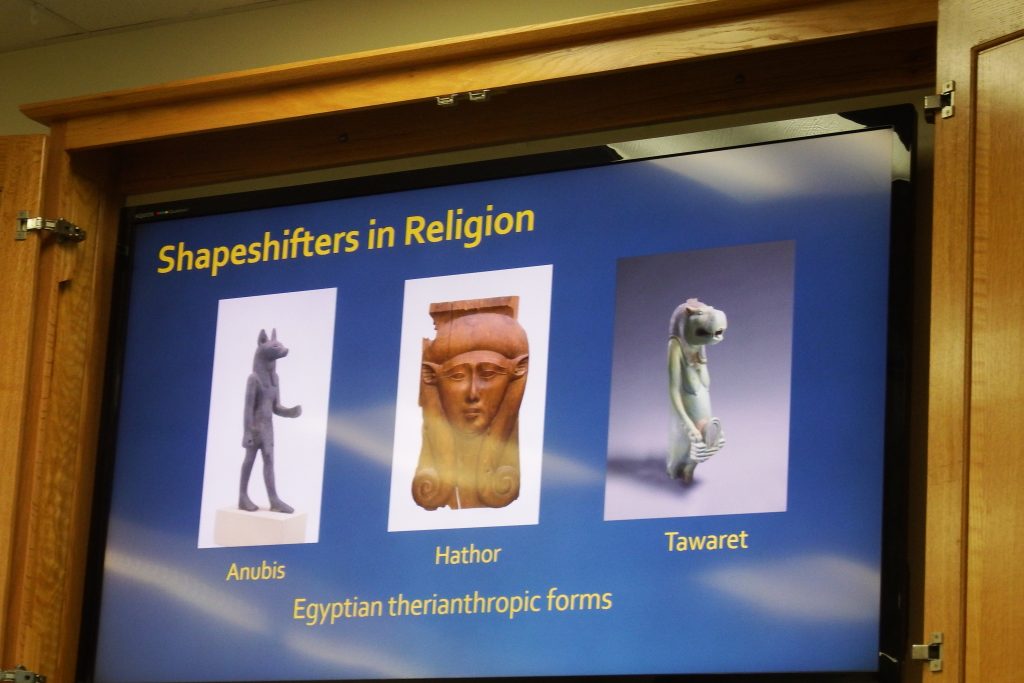

Next up was Egyptian therianthropy. These human-animal hybrids were believed to inhabit statues. But, except for that small fact, they could have been taken straight out of modern urban fantasy. Isn’t it Patricia Briggs’ werewolves who can take on a wolf-man hybrid form for battle?

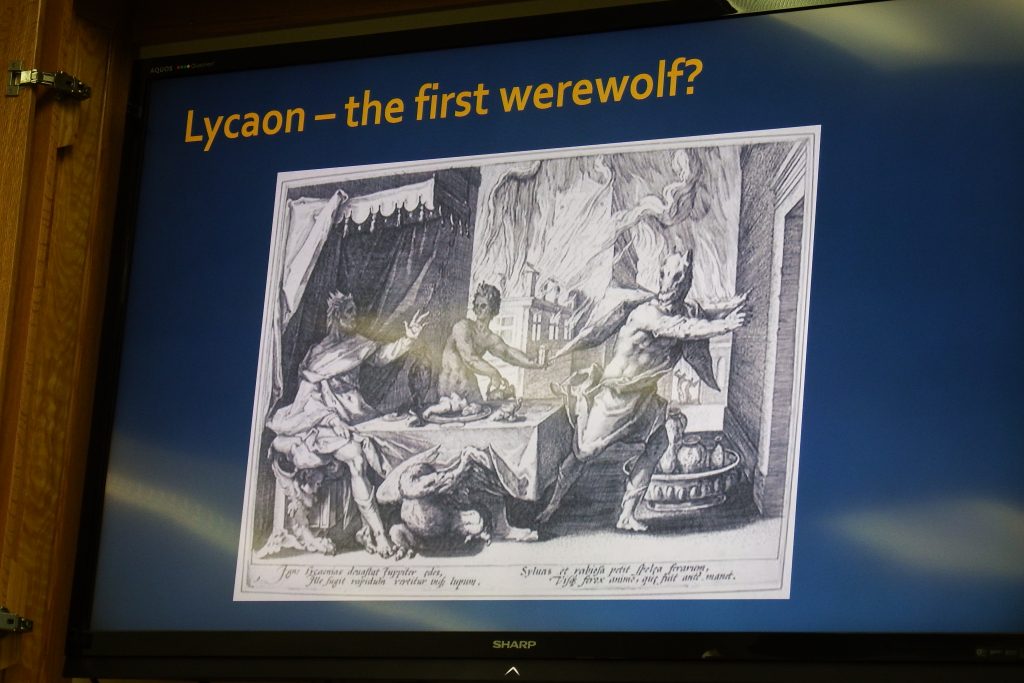

Greek and Roman mythologies were even more full of shapeshifters, with gods taking the form of bulls, swans, and many other animals. In most cases, the gods shifted to seduce women. (Because, you know, a bird is so much sexier than a human male….) In others, gods shifted mortals into plants to help the latter escape a similar fate.

Then Kachuba went out on a bit of a limb. He argued that there were shifters in the Christian Bible, starting with Nebuchadnezzar and possibly extending to Jesus himself. Similarly, he read Buddhist texts that suggested Buddha had transfigured at least twice. At which point Kachuba jumped over to Hinduism to mention Vishnu’s many forms.

Except for Nebuchadnezzar, all of these transformations were from human to human rather than from human to animal. But the religious history does beg the question — where do you draw the line about what counts as a shifter and what does not?

Religious hair-splitting aside, there have even been near-modern accounts of shapeshifters. For example, the Beast of Gevadaun killed more than a hundred people in one year in eighteenth century France. A New York Times article suggested that a werewolf was killing children in India in 1996. And modern vampire communities still exist in New Orleans and Buffalo, New York, with volunteers donating blood to “vampires” who believe they need this fluid to keep them alive.

(Kachuba included vampires in his shapeshifter history because of their reputation of transforming into bats.)

Our lecturer was starting to run out of time when he branched out beyond Western shapeshifters. But he did mention Navajo skinwalkers, along with the vast quantity of shifters included in Japanese lore. (If you’ve read my Moon Marked series, you’ve learned about one of the most common examples of the latter — the kitsune, a fox shifter.)

To Kachuba’s list, I would add some of the other historical shifters which have caught my attention in recent months. The selkie (seal shifter) has always fascinated me, even more so when I learned that Croatian lore has a werewolf version of this tale. (You’ll find out what I made of that in December!) Kelpies are water horses that transform into women. Naga are snake shifters in India. And some Chinese stories have humans shifting into the form of dogs.

But — why? Why do shapeshifter legends span so many cultures? Kachuba suggested a few possible explanations.

In my books, I often like to play with the dual nature of shapeshifters — animal vs. civilized human — and this may be the psychological root of some legends. But shapeshifting also offers us a way to hide, to understand personal transformation, to attain new knowledge (especially in shamanic beliefs), and to excuse bad behavior (Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde style). There is also a trickster side to many shapeshifter archetypes, which may be related to some or all of the above.

Which, I know, sounds pretty esoteric when written out in the form of a list. But think of it this way — how did you feel as a kid when you dressed up for Halloween? Didn’t you, in some metaphorical manner, shift your skin? If so, I hope you’ll click over to Facebook and tell me all about it!