Since today is my birthday, I thought you might indulge me sharing an old family story that contains no werewolves or supernatural elements. This essay was written by 17-year-old me as part of an application for a scholarship from the Daughters of the American Revolution.

(No, they didn’t give me the scholarship. I can’t imagine why not.)

***

Most of my mother’s ancestors were blond, blue-eyed people. They traced their descent on her father’s side from Sweden and on her mother’s from Saxon stock. So the question arose: Why did my grandmother, my mother, and I all have dark hair and eyes?

Once, my grandmother was told by her angry grandmother that she was just like “that woman” with her dark hair and snapping black eyes. At the time, a woman was expected to be meek and obliging, not willful and defiant.

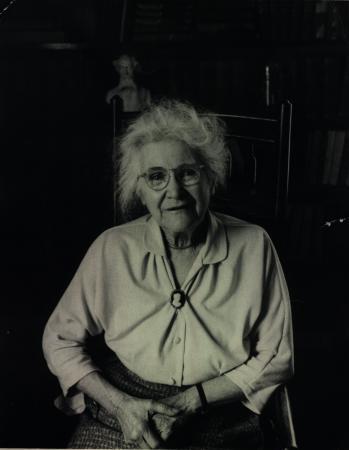

My grandmother showed me a picture of “that woman,” who turned out to be Mary Greene, my great-great-great grandmother. The photograph was black and white and much faded with age, but I could easily distinguish the woman who my grandmother was supposed to resemble. Mary Greene’s hair was white and the old woman sat peacefully in a large chair. And yet, I saw the same pride in her face that I often see in my grandmother’s, the pride I hope to find in my own face.

I think this is the picture 17-year-old-me was referring to…but if so I was a bad listener. This is my great-grandmother.

The Greenes, so the story goes, lived in Hope Valley, Rhode Island, and often went to Shawomet, by the shore. Some of my relatives remember picnics at the traditional family farm in Rhode Island. However, the Greenes lived long before the memories of these relatives, in a simpler time when people walked the few miles to the beach to sharpen their scythes in the sand.

I like to imagine that these distant ancestors were good people, and their deeds certainly seem to indicate kindness. After one of the violent storms that blew in off the ocean, the Greenes found a shipwrecked girl tossed up on the beach and took her in. Their dark-complexioned foundling was named Mary Greene and, although she was well-loved, she never quite blended into the family. She looked different; but, more than that, she was independent.

Mary Greene grew up and lost some of her impulsiveness, although she was never a conventional woman. She married a blond Yankee like those in her adopted family and soon they had four small children, each of whom kept at least a small part of Mary Greene’s features and will. Her third child named his first child Mary Greene after her grandmother. However, the girl’s mother believed, as most people did at that time, that a woman should be tractable and obedient. Therefore, Mary Greene the elder’s daughter-in-law was never in accord with her new mother-in-law.

The willful streak of darkness slipped down through the generations until my grandmother stamped her foot angrily and was told by that daughter-in-law (now a grandmother) that she was just like “that woman,” the defiant waif who family lore supposed was Spanish or Portuguese or perhaps Native American.

Mary Greene was a woman born at the wrong time, but her descendants inherited the fortitude and defiance necessary to survive in twentieth century America. That willful, wonderful woman imparted to my grandmother the ability to travel to Panama as a dietician at a time when many women didn’t have jobs outside the home, let alone outside the country. I am anticipating with pleasure the ability Mary Greene has bequeathed to me.

***

In case you’re curious, a DNA test of my mother combined with some genealogical sleuthing suggests that “that woman” was likely of Germanic descent. An odd coincidence since my father’s side of the family is largely from Austria and Germany and is also dark-haired and dark-eyed.

But that — including the butcher who could write two different letters with his right and left hands at the same time — is a story for another time.